Eating in the dark

What do you see when you eat? Usually we see many things at once: the food, a friend, a view, a painting of a view, or maybe a fork that was supposed to have food on it but does not. Some of us read while we eat. (After decades of this habit, I’ve gotten to the point where the words on a page now have a taste of their own.) Once in a while, however, we eat in the dark, and see nothing at all.

I've eaten a number of times in near-darkness, usually when the power goes out. Once, as a child, I blindfolded myself and spent a summer afternoon stumbling around inside our farmhouse for some now-forgotten reason. Most of my memories from that experiment are hazy at best: a red bandana over my eyes, hesitant steps with my fingers outstretched, the sound of mice running behind the walls. What I do remember sharply, however, is the taste of the one thing that I managed to eat that afternoon: tart pickles from a jar. But in that experiment there was a still a bit of light filtering in between the threads of the cloth over my eyes.

Some restaurants serve food in very dim lighting. In

It is one thing to eat in near darkness, and another to eat in pitch darkness. In the past ten years, a number of restaurants have opened that offer diners the chance to eat in the complete absence of light. These include unsicht-Bar in Berlin, Blindekuh (“Blind Cow”) in Berlin, Opaque in Los Angeles, and Whale Inside in Beijing.

Eating in complete darkness changes how you eat. For one thing, you are now dependent on others to tell you what you are eating, and where your food is, and where you may sit. Waiters take a more active role in your meal. They assist in getting you into your seat, and remain nearby in case you lose track of a utensil or begin to panic in the dark. At some restaurants, such as Dans le Noir in

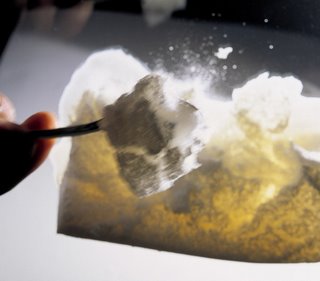

Not every dark restaurant will tell you what you are eating in advance. For example, unsicht-Bar provides descriptions that range from unhelpful (“Crispy fellows prefer to float on this intoxicated, gilded sea”) to completely inscrutable (“Multi-continental meeting of illustrious ingredients”). The visual design – and color – of the chef’s plating is now unnecessary. The ubiquitous calligraphy of sauces that decorate plates would only end up on fingers and cuffs. Tall food is no longer whimsical, but hazardous.

Having someone feed you while blindfolded may be sexy, but feeding yourself in the dark is decidedly unattractive. When no one can see you, the temptation to abandon your lost silverware and eat with your hands is too great. This could be potentially disastrous, if it’s not something you know how to do. Diners at dark restaurants are advised to dress down, as they usually end up wearing a good part of their meal.

One question that comes to mind is why anyone would want to put up with any of this. The thinking behind these restaurants varies. Some restaurants aim to build empathy for the blind. Others focus on the experience and the heightened senses. (One restaurant’s motto is “Darkness leads to truthfulness about taste.”) Not surprisingly, dark restaurants are popular places for “blind” dates. If things go badly, you could quietly sneak away while your date is still in mid-anecdote.

Seeing is important because it is how we know that the food before us is good to eat. We look not only at our food, but also at those who around us at the time. When Mani was an infant, he would stare hard at whoever was feeding him at the time. It is usually disconcerting to have someone stare at you like that, but a child’s guileless gaze is something you can fall into and get lost inside. I think that when a child does this, he or she is making an imprint of the moment, remembering who is providing good, safe food. As adults, we continue to look to others’ faces for indications of whether food is not only safe, but delicious. It is no coincidence that the parts of the brain that process facial expressions of disgust, the insula, also have a role in processing taste and generating cravings.

I think the next frontier in sensory deprivation dining is to have restaurants where you not only cannot see the food, but you cannot taste it either. They would still charge for the smell of the food, but -- as the parable goes -- you can just pay with the sound of money.

-778438-778475.jpg)